Article: 'Laying the Ghost of Welfare Paternalism' by Ken Davis (c. 1990)

Celebrating UPIAS's 50th Anniversary: Part 10

About the Series:

The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) was formed in September 1972, after Paul Hunt wrote letters to different newspapers and magazines asking disabled people to help set up a new organisation.

Hunt first suggested that this should be a ‘consumer group’ to look at the different kinds of support disabled people were getting and decide which gave them the most control over their lives. UPIAS quickly became much more than that. The group brought together disabled people who were sick of being let down by poor housing, segregated education, campaigns about ‘disability’ that were led by non-disabled people, and new kinds of ‘help’ from charities and governments that didn’t bother to ask them what they needed or wanted.

They decided that they needed to get to the bottom of why disabled people got such a bad deal: why were they so often poor; why were physical buildings and public spaces built in a way that shut them out; why were they kept separated from non-disabled people in special Homes, hospitals, clubs, and transport; why did non-disabled people think they had a right to make decisions about their lives?

During these discussions, UPIAS members realised that this inequality had nothing to do with their bodies or minds being different to anyone else’s. With the state of technology and know-how in the 1970s, there was no reason why a wheelchair user, a blind person, someone with no hearing, a pain condition, etc, couldn’t get a job, an appropriate house adapted, or use public transport if it was adapted for their mobility needs. This meant that there is a difference between an impairment – a person’s body or mind being different to other people’s – and their disability – the fact that society is designed in such a way that they are stopped from doing what other people do.

This idea, which was later called the "social model of disability" inspired the Disabled People’s Movement in Britain and worldwide. UPIAS members understood that the only way to change their exclusion was to change society and that only disabled people could see what changes needed to be made. They brought the idea to their local work, setting up Coalitions and Centres for Integrated Living, and made the idea national when they helped form the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). Through BCODP, the social model went global, when British delegates convinced members of the Disabled People’s International of their analysis in the early 1980s.

Despite these achievements, a lot of articles written by UPIAS members have been out of print for decades. To celebrate UPIAS’s influence on us as disabled activists, we will be publishing articles by UPIAS members each week for the next two months to help activists today better understand our history. Each article will be free to download, with large print and easier-to-read versions alongside a text only, screen-reader friendly version of the original.

This Article

This article, by Ken Davis, was written in the context of the Health Services and Community Care Bill, which eventually became the 1990 NHS and Community Care Act, going through Parliament. Davis gives an overview of the history of the welfare state and laws concerning services for disabled people, and argues that 'welfare paternalism' is an ideology underpinning it that forms a core part of disabled people's oppression and exclusion from the democratic process, and which therefore the Disabled People's Movement needs to vigorously oppose.

14pt Laying the Ghost of Welfare Paternalism - Ken Davis

18pt Laying the Ghost of Welfare Paternalism - Ken Davis

Easier to Read - Laying the Ghost of Welfare Paternalism

Article: 'What to do?' by Vic Finkelstein (2000)

Celebrating UPIAS's 50th Anniversary: Part 8

About the Series:

The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) was formed in September 1972, after Paul Hunt wrote letters to different newspapers and magazines asking disabled people to help set up a new organisation.

Hunt first suggested that this should be a ‘consumer group’ to look at the different kinds of support disabled people were getting and decide which gave them the most control over their lives. UPIAS quickly became much more than that. The group brought together disabled people who were sick of being let down by poor housing, segregated education, campaigns about ‘disability’ that were led by non-disabled people, and new kinds of ‘help’ from charities and governments that didn’t bother to ask them what they needed or wanted.

They decided that they needed to get to the bottom of why disabled people got such a bad deal: why were they so often poor; why were physical buildings and public spaces built in a way that shut them out; why were they kept separated from non-disabled people in special Homes, hospitals, clubs, and transport; why did non-disabled people think they had a right to make decisions about their lives?

During these discussions, UPIAS members realised that this inequality had nothing to do with their bodies or minds being different to anyone else’s. With the state of technology and know-how in the 1970s, there was no reason why a wheelchair user, a blind person, someone with no hearing, a pain condition, etc, couldn’t get a job, an appropriate house adapted, or use public transport if it was adapted for their mobility needs. This meant that there is a difference between an impairment – a person’s body or mind being different to other people’s – and their disability – the fact that society is designed in such a way that they are stopped from doing what other people do.

This idea, which was later called the "social model of disability" inspired the Disabled People’s Movement in Britain and worldwide. UPIAS members understood that the only way to change their exclusion was to change society and that only disabled people could see what changes needed to be made. They brought the idea to their local work, setting up Coalitions and Centres for Integrated Living, and made the idea national when they helped form the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). Through BCODP, the social model went global, when British delegates convinced members of the Disabled People’s International of their analysis in the early 1980s.

Despite these achievements, a lot of articles written by UPIAS members have been out of print for decades. To celebrate UPIAS’s influence on us as disabled activists, we will be publishing articles by UPIAS members each week for the next two months to help activists today better understand our history. Each article will be free to download, with large print and easier-to-read versions alongside a text only, screen-reader friendly version of the original.

This Article

This article, by Vic Finkelstein, is a critique of the Disabled People’s Movement and it’s leadership in the late 1990s from the perspective of UPIAS’s radical theory. Finkelstein argues that the leadership’s focus on parliament to win reforms, combined with disabled academics’ insistence that the social model must be more person centred, has robbed the Movement of its radicalism. Instead of a broad, grassroots movement to change the world, Finkelstein argues, the Movement was at risk of falling into elitism. Most activists were not involved in deciding what the Movement should do, and the social model (which should have helped them decide their own priorities and strategy) was being turned into something that talked about feelings and identity instead of the social world. Finkelstein argues that, to really make itself democratic, the Movement must look out to the struggles of workers and climate activists; learning from their ways of working and making the fight against disablement part of their struggles.

Easier to read Vic Finkelstein - What to do (2000)

Article: 'Mainstreaming - The Necessity of Republicanism' by Dick Leaman (1996)

Celebrating UPIAS's 50th Anniversary: Part 7

About the series:

The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) was formed in September 1972, after Paul Hunt wrote letters to different newspapers and magazines asking disabled people to help set up a new organisation.

Hunt first suggested that this should be a ‘consumer group’ to look at the different kinds of support disabled people were getting and decide which gave them the most control over their lives. UPIAS quickly became much more than that. The group brought together disabled people who were sick of being let down by poor housing, segregated education, campaigns about ‘disability’ that were led by non-disabled people, and new kinds of ‘help’ from charities and governments that didn’t bother to ask them what they needed or wanted.

They decided that they needed to get to the bottom of why disabled people got such a bad deal: why were they so often poor; why were physical buildings and public spaces built in a way that shut them out; why were they kept separated from non-disabled people in special Homes, hospitals, clubs, and transport; why did non-disabled people think they had a right to make decisions about their lives?

During these discussions, UPIAS members realised that this inequality had nothing to do with their bodies or minds being different to anyone else’s. With the state of technology and know-how in the 1970s, there was no reason why a wheelchair user, a blind person, someone with no hearing, a pain condition, etc, couldn’t get a job, an appropriate house adapted, or use public transport if it was adapted for their mobility needs. This meant that there is a difference between an impairment – a person’s body or mind being different to other people’s – and their disability – the fact that society is designed in such a way that they are stopped from doing what other people do.

This idea, which was later called the "social model of disability" inspired the Disabled People’s Movement in Britain and worldwide. UPIAS members understood that the only way to change their exclusion was to change society and that only disabled people could see what changes needed to be made. They brought the idea to their local work, setting up Coalitions and Centres for Integrated Living, and made the idea national when they helped form the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). Through BCODP, the social model went global, when British delegates convinced members of the Disabled People’s International of their analysis in the early 1980s.

Despite these achievements, a lot of articles written by UPIAS members have been out of print for decades. To celebrate UPIAS’s influence on us as disabled activists, we will be publishing articles by UPIAS members each week for the next two months to help activists today better understand our history.

Each article will be free to download, with large print and easier-to-read versions alongside a text-only, screen-reader-friendly version of the original.

This Week

This week we return to Dick Leaman, General Secretary of UPIAS until it dissolved in 1990. In this article, Leaman argues that the Disabled People’s Movement is running out of steam; with its leaders moving further away from what disabled activists demand, and becoming out of touch with the inequalities in the world around them. Instead of seeking to make disabled people part of mainstream society as it is now, Leaman urges the Disabled People’s Movement to focus on changing society – challenging inequality, privilege, and oppression everywhere they appear, and not just as they effect disabled people.

14pt. Mainstreaming - The Necessity of Republicanism by Dick Leaman

18pt. Mainstreaming - The Necessity of Republicanism by Dick Leaman

Easier to Read - Mainstreaming

Articles: 'Service Brokerage Parts 1 & 2' by Ken Lumb & 'Service Brokerage - Power to the Pedlars' by Ken Davis (1989)

Celebrating UPIAS's 50th Anniversary: Part 6

About the Series:

The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) was formed in September 1972, after Paul Hunt wrote letters to different newspapers and magazines asking disabled people to help set up a new organisation.

Hunt first suggested that this should be a ‘consumer group’ to look at the different kinds of support disabled people were getting and decide which gave them the most control over their lives. UPIAS quickly became much more than that. The group brought together disabled people who were sick of being let down by poor housing, segregated education, campaigns about ‘disability’ that were led by non-disabled people, and new kinds of ‘help’ from charities and governments that didn’t bother to ask them what they needed or wanted.

They decided that they needed to get to the bottom of why disabled people got such a bad deal: why were they so often poor; why were physical buildings and public spaces built in a way that shut them out; why were they kept separated from non-disabled people in special Homes, hospitals, clubs, and transport; why did non-disabled people think they had a right to make decisions about their lives?

During these discussions, UPIAS members realised that this inequality had nothing to do with their bodies or minds being different to anyone else’s. With the state of technology and know-how in the 1970s, there was no reason why a wheelchair user, a blind person, someone with no hearing, a pain condition, etc, couldn’t get a job, an appropriate house adapted, or use public transport if it was adapted for their mobility needs. This meant that there is a difference between an impairment – a person’s body or mind being different to other people’s – and their disability – the fact that society is designed in such a way that they are stopped from doing what other people do.

This idea, which was later called the "social model of disability" inspired the Disabled People’s Movement in Britain and worldwide. UPIAS members understood that the only way to change their exclusion was to change society and that only disabled people could see what changes needed to be made. They brought the idea to their local work, setting up Coalitions and Centres for Integrated Living, and made the idea national when they helped form the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). Through BCODP, the social model went global, when British delegates convinced members of the Disabled People’s International of their analysis in the early 1980s.

Despite these achievements, a lot of articles written by UPIAS members have been out of print for decades. To celebrate UPIAS’s influence on us as disabled activists, we will be publishing articles by UPIAS members each week for the next two months to help activists today better understand our history. Each article will be free to download, with large print and easier-to-read versions alongside a text only, screen-reader friendly version of the original.

This Week’s Post

This week we return to Ken Davis and Ken Lumb, and to the question of the reforms proposed by non-disabled professionals for social care services in the late ‘8os and early ‘90s. In these articles, first published in Coalition, Davis and Lumb take aim at the private companies, charities, and social services departments who were peddling ‘service brokerage’ – an early form of what became ‘care management’ after the Community Care Act in 1990. While these groups pointed, rightly, to disabled people’s lack of choice or control over the services they used; Davis and Lumb argue that this whole project is not to empower disabled people, but to head off their radical demands by offering minor changes to an oppressive system. In Davis and Lumb's view, the move to buying and selling services on an open market, with funding made available per person, simply forces disabled people to choose between bad services over which they have no control, while leaving power over what is available in the hands of non-disabled people. At the same time, schemes like service brokerage undermine the Disabled People’s Movement’s insistence on disabled people working out solutions to their problems democratically as a group in society, rather than as isolated individuals.

14 pt Service Brokerage Parts 1 & 2 by Ken Lumb

18 pt Service Brokerage Parts 1 & 2 by Ken Lumb

Easier to Read Service Brokerage Parts 1 and 2 by Ken Lumb

14 pt Service Brokerage - Power to the Pedlars by Ken Davis

18 pt Service Brokerage - Power to the Pedlars by Ken Davis

Easier to Read Service Brokerage Power to the Pedlars by Ken Davis

Article: Dick Leaman - The Commodity of Care (1990)

Celebrating UPIAS's 50th Anniversary: Part 5

About this Series

The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) was formed in September 1972, after Paul Hunt wrote letters to different newspapers and magazines asking disabled people to help set up a new organisation.

Hunt first suggested that this should be a ‘consumer group’ to look at the different kinds of support disabled people were getting and decide which gave them the most control over their lives. UPIAS quickly became much more than that. The group brought together disabled people who were sick of being let down by poor housing, segregated education, campaigns about ‘disability’ that were led by non-disabled people, and new kinds of ‘help’ from charities and governments that didn’t bother to ask them what they needed or wanted.

They decided that they needed to get to the bottom of why disabled people got such a bad deal: why were they so often poor; why were physical buildings and public spaces built in a way that shut them out; why were they kept separated from non-disabled people in special Homes, hospitals, clubs, and transport; why did non-disabled people think they had a right to make decisions about their lives?

During these discussions, UPIAS members realised that this inequality had nothing to do with their bodies or minds being different to anyone else’s. With the state of technology and know-how in the 1970s, there was no reason why a wheelchair user, a blind person, someone with no hearing, a pain condition, etc, couldn’t get a job, an appropriate house adapted, or use public transport if it was adapted for their mobility needs. This meant that there is a difference between an impairment – a person’s body or mind being different to other people’s – and their disability – the fact that society is designed in such a way that they are stopped from doing what other people do.

This idea, which was later called the "social model of disability" inspired the Disabled People’s Movement in Britain and worldwide. UPIAS members understood that the only way to change their exclusion was to change society and that only disabled people could see what changes needed to be made. They brought the idea to their local work, setting up Coalitions and Centres for Integrated Living, and made the idea national when they helped form the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). Through BCODP, the social model went global, when British delegates convinced members of the Disabled People’s International of their analysis in the early 1980s.

Despite these achievements, a lot of articles written by UPIAS members have been out of print for decades. To celebrate UPIAS’s influence on us as disabled activists, we will be publishing articles by UPIAS members each week for the next two months to help activists today better understand our history.

Each article will be free to download, with large print and easier-to-read versions alongside a text-only, screen-reader-friendly version of the original.

This week:

The DPA are delighted to publish an article by Dick Leaman, an early member of UPIAS and one of the founders of the Lambeth Coalition of Disabled People and the Centre for Integrated Living; as well as an active member of other DPOs in South London in the 1980s and ‘90s.

Here, Leaman looks at the Tory government’s plans from to turn social care into something that is bought and sold, instead of provided by the state. Despite the government claiming it had an agenda for ‘Community Care’, Leaman argues its reforms have nothing to do with either ‘community’ or ‘care’. They are simply a financial reform, designed to make it easier to make social care cheaper and to cut taxes for the rich and powerful. According to Leaman, the government had opted out of discussions about what social care should look like, what services should be offered to disabled people, and who should make the decisions about what does and doesn’t happen in the sector.

The government’s retreat from these debates, Leaman argues, presents great risks and great opportunities for disabled people. Reforms to services are likely to mean cuts, and new battles between the disabled people’s movement and local councils over what is available. If the movement wins those battles, though, the fact that central government does not want to interfere gives them the chance to radically change the way support services are designed and provided.

This article was published in the September 1990 issue of GMCDP’s Coalition magazine.

Links to different version of this article are below:

14pt. The Commodity of Care by Dick Leaman

18pt. The Commodity of Care by Dick Leaman

Easier to Read - The Commodity of Care

Article: Ken Lumb - Telethon, Connecting the Means to the Ends (1992)

Celebrating UPIAS's 50th Anniversary: Part 4

About the Series:

The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) was formed in September 1972, after Paul Hunt wrote letters to different newspapers and magazines asking disabled people to help set up a new organisation.

Hunt first suggested that this should be a ‘consumer group’ to look at the different kinds of support disabled people were getting and decide which gave them the most control over their lives. UPIAS quickly became much more than that. The group brought together disabled people who were sick of being let down by poor housing, segregated education, campaigns about ‘disability’ that were led by non-disabled people, and new kinds of ‘help’ from charities and governments that didn’t bother to ask them what they needed or wanted.

They decided that they needed to get to the bottom of why disabled people got such a bad deal. Why were they so often poor? Why were physical buildings and public spaces built in a way that shut them out? why were they separated from non-disabled people in special Homes, hospitals, clubs, and transport? Why did non-disabled people think they had a right to make decisions about their lives?

During these discussions, they realised that this inequality had nothing to do with their bodies or minds being different to anyone else’s. With the state of technology and know-how in the 1970s, there was no reason why a wheelchair user, a blind person, someone with no hearing, a pain condition, etc, couldn’t get a job, an appropriate house adapted, or use public transport if it was adapted for their mobility needs. This meant that there is a difference between an impairment – a person’s body or mind being different to other people’s – and their disability – the fact that society is designed in such a way that they are stopped from doing what other people do.

This idea, later called the "social model of disability", inspired the Disabled People’s Movement in Britain and worldwide. UPIAS members understood that the only way to change their exclusion was to change society and that only disabled people could see what changes needed to be made. They brought the idea to their local work, setting up Coalitions and Centres for Integrated Living, and made the idea national when they helped form the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). Through BCODP, the social model went global, when British delegates convinced members of the Disabled People’s International of their analysis in the early 1980s.

Despite these achievements, a lot of articles written by UPIAS members have been out of print for decades. To celebrate UPIAS’s influence on us as disabled activists, we will be publishing articles by UPIAS members each week for the next two months to help activists today better understand our history. Each article will be free to download, with large print and easier-to-read versions alongside a text only, screen-reader friendly version of the original.

This Week:

Our article this week is from Ken Lumb, a member of both UPIAS and the Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People and an editor of its magazine Coalition – which this article was written for.

In the early ‘90s, the Disabled People’s Movement was involved in a massive campaign against the patronising and offensive depictions of disabled people used by charities for fundraising events. This campaign reached its height in the huge demonstrations against Telethon – a television fundraising event – in 1992. Lumb sums up the arguments used by disabled activists against Telethon, before looking at the thorny issue of how Disabled People’s Organisations fund themselves. Some groups of activists, despite their dislike of disability charities, had felt that they had no option except to take money from them in order to survive. Lumb explains why he believes this is damaging to the movement as a whole, before arguing that the movement needs to find new ways to divide up work and resources amongst its member groups to protect them from outside influence.

Links to read these are below:

14 pt Telethon Connecting the Means to the Ends by Ken Lumb

18 pt Telethon Connecting the Means to the Ends by Ken Lumb

Easier to Read Telethon Connecting the Means with the Ends by Ken Lumb

Article: ‘The Politics of Independent Living – Keeping the Movement Radical’ by Ken Davis (1984)

Celebrating UPIAS’s 50th Anniversary: Part 2

About the series:

The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) formed in September 1972, after Paul Hunt wrote letters to different newspapers and magazines asking disabled people to help set up a new organisation.

Hunt first suggested that this should be a ‘consumer group’ to look at the different kinds of support disabled people were getting and decide which gave them the most control over their lives. UPIAS quickly became much more than that. The group brought together disabled people who were sick of being let down by poor housing, segregated education, campaigns about ‘disability’ that were led by non-disabled people, and new kinds of ‘help’ from charities and governments that didn’t bother to ask them what they needed or wanted.

They decided that they needed to get to the bottom of why disabled people got such a bad deal: why were they so often poor?; why were physical buildings and public space built in a way that shut them out?; why were they kept separated from non-disabled people in special Homes, hospitals, clubs, and transport?; why did non-disabled people think they had a right to make decisions about their lives?

During these discussions, UPIAS members realised that this inequality had nothing to do with their bodies or minds being different to anyone else’s. With the state of technology and know-how in the 1970s, there was no reason why a wheelchair user, a blind person, someone with no hearing, a pain condition, etc, couldn’t get a job, an appropriate house adapted, or use public transport if it was adapted for their mobility needs. This meant that there is a difference between an impairment – a person’s body or mind being different to other people’s – and their disability – the fact that society is designed in such a way that they are stopped from doing what other people do.

This idea, which was later called the ‘social model of disability’, inspired the Disabled People’s Movement in Britain and worldwide. UPIAS members understood that the only way to change their exclusion was to change society, and that only disabled people could see what changes needed to be made. They brought the idea to their local work, setting up Coalitions and Centres for Integrated Living, and made the idea national when they helped form the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). Through BCODP, the social model went global, when British delegates convinced members of the Disabled People’s International of their analysis in the early 1980s.

Despite these achievements, a lot of articles written by UPIAS members have been out of print for decades. To celebrate UPIAS’s influence on us as disabled activists, we will be publishing articles by UPIAS members each week for the next two months to help activists today better understand our history. Each article will be free to download, with large print and easier-to-read versions alongside a text only, screen-reader friendly version of the original.

This Week:

The DPA are delighted to publish an article by Ken Davis, an early member of UPIAS and one of the founders of the Derbyshire Coalition of Disabled and the Derbyshire Centre for Integrated Living. Ken and his partner Maggie Hines (later Davis) had helped to start independent living projects in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire in the ‘70s and ‘80s; working with other disabled people and local councils and housing associations to work out how normal flats and bungalows could be adapted so that disabled people could live in them and finding new ways for tenants to get the support they need without having to go into a care home.

During the International Year of Disabled People in 1981, Ken and Maggie were able to get disabled activists across Derbyshire together into one group – the Coalition – and to persuade the County Council that disabled people had a right to be consulted on all the state services they used. A few years later, this understanding created Britain’s first Centre for Integrated Living (CIL). The idea was simple, but revolutionary: workers and volunteers from the CIL met with local people around the county and asked them what they needed to have more control over their lives. Then, the CIL would design a service with the council which gave them what they needed. This was the first time in Britain that disabled people in a local area had a real say over what local government’s gave them, and it flew in the face of the usual way of working where charities, academics, professionals and governments made all the decisions between them.

Not everyone was happy though. This way of doing things brought disabled people to the centre of how local services work; but it cut out the charities, researchers, and academics. Academics, in particular, were openly critical of schemes around the world to base services around disabled people. In this article, Ken Davis deals with one example of what he calls the academic ‘reaction’ – Gareth Williams’ attack on the Independent Living Movement in America. Davis argues that academic critiques of disabled people’s demands for more freedom over their lives are not based on objective fact or careful, scientific reasoning; but are a wholly political attempt to side-line disabled people and restore professional dominance.

This article was first published in Derbyshire Coalition of Disabled People News in 1984. The version we have used for transcription comes the UPIAS Members’ Pack – a collection of articles the Union sent to all members to explain the organisation’s views and analysis.

Links to read these are below:

14pt. The Politics of Independent Living - Screen Reader Friendly

18pt. The Politics of Independent Living - Screen Reader Friendly

Easier to Read - The Politics of Independent Living - Screen Reader Friendly

Article: 'Disability - A Capitalist By-product' by Two UPIAS Members (1981)

Celebrating UPIAS’s 50th Anniversary: Part 1

About the Series:

The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) was formed in September 1972, after Paul Hunt wrote letters to different newspapers and magazines asking disabled people to help set up a new organisation.

Hunt first suggested that this should be a ‘consumer group’ to look at the different kinds of support disabled people were getting and decide which gave them the most control over their lives. UPIAS quickly became much more than that. The group brought together disabled people who were sick of being let down by poor housing, segregated education, campaigns about ‘disability’ that were led by non-disabled people, and new kinds of ‘help’ from charities and governments that didn’t bother to ask them what they needed or wanted.

They decided that they needed to get to the bottom of why disabled people got such a bad deal: why were they so often poor; why were physical buildings and public spaces built in a way that shut them out; why were they kept separated from non-disabled people in special Homes, hospitals, clubs, and transport; why did non-disabled people think they had a right to make decisions about their lives?

During these discussions, UPIAS members realised that this inequality had nothing to do with their bodies or minds being different to anyone else’s. With the state of technology and know-how in the 1970s, there was no reason why a wheelchair user, a blind person, someone with no hearing, a pain condition, etc, couldn’t get a job, an appropriate house adapted, or use public transport if it was adapted for their mobility needs. This meant that there is a difference between an impairment – a person’s body or mind being different to other people’s – and their disability – the fact that society is designed in such a way that they are stopped from doing what other people do.

This idea, which was later called the "social model of disability" inspired the Disabled People’s Movement in Britain and worldwide. UPIAS members understood that the only way to change their exclusion was to change society and that only disabled people could see what changes needed to be made. They brought the idea to their local work, setting up Coalitions and Centres for Integrated Living, and made the idea national when they helped form the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). Through BCODP, the social model went global, when British delegates convinced members of the Disabled People’s International of their analysis in the early 1980s.

Despite these achievements, a lot of articles written by UPIAS members have been out of print for decades. To celebrate UPIAS’s influence on us as disabled activists, we will be publishing articles by UPIAS members each week for the next two months to help activists today better understand our history. Each article will be free to download, with large print and easier-to-read versions alongside a text only, screen-reader friendly version of the original.

This Week:

The DPA is proud to publish a short introduction to UPIAS’s thought from 1981, written by two anonymous members for Big Flame – a Marxist newspaper in Britain. In it, the two members argue that disability is caused by how society is organised around a capitalist economy. Capitalism, they show, creates both impairment and disability through the ever-changing types of work people are forced to do, the way everything from housing and transport to health were made to help businesses make profits, and the way that competitive societies rob people of their individuality and freedom to choose what the world should look like.

Links to read these are below:

Easier to Read - Disability - A Capitalist by-product - Screen Reader Friendly

The Big Disability Survey 2022

The Greater Manchester Disabled People’s Panel has launched the ‘Big Disability Survey 2022’. The survey, which launched on Tuesday 28 June, is targeted at any disabled people who live or work across Greater Manchester and specifically aims to find out your attitudes and feelings towards the current cost of living crisis.

The survey builds on the 2020 survey from the Panel, which saw nearly 1,000 disabled people in Greater Manchester respond about their views on the Covid-19 pandemic. The findings of the last survey where 90% of respondents said that the pandemic had a negative impact on their mental health, has helped the panel to apply pressure to decision makers about the services available to them. The 2020 survey also raised big issues with digital exclusion, as much of the emergency response was relying on digital platforms. This insight has helped to develop Greater Manchester’s response to digital inclusion.

The new 2022 survey focuses on the challenges people might face relating to the current cost of living. Whilst it is an online survey, the Panel are encouraging people to complete the survey in whichever way suits them, with postal, BSL and in-person support available if people need it.

The Greater Manchester Disabled People's Panel is made up of 15 Disabled People's organisations, run by and for disabled people. The results of this survey will help influence policy and make our city-region a better place to live for disabled people. The more disabled people who can fill it in, the stronger their voice for change becomes.

The insight this survey will provide, will hopefully help shape services and provision in the future.

To complete the survey visit www.gmbigdisabilitysurvey.com

There is more information on the GM Disabled People's Panel website and there is a BSL video about the survey.

For support with completing the survey –

Email – panel [at] gmcdp.com

Text or call – 07367 754595

Alternatively, written responses can be sent to –

GMCDP, Unit 4

Windrush Millennium Centre

70 Alexandra Road

Manchester

M16 7WD

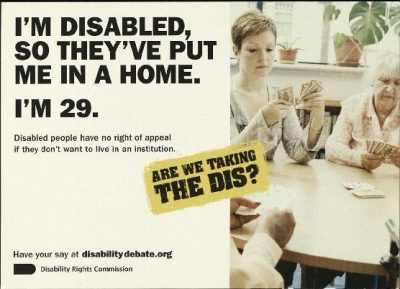

Postcard: They've put me in a home, Are We Taking the Dis?, 2005

About

The Disability Rights Commission ran the ‘Are we taking the dis?’ campaign in 2005 to raise awareness of discrimination against disabled people. The national campaign ran for 6 weeks and cost £1.2million. The Disability Rights Commission website received 535% more hits because of the campaign.

Image description

Left side reads “I'm disabled, so they've put me in a home. I'm 29. Disabled people have no right of appeal if they don't want to live in an institution."

Underneath is a yellow logo that reads “Are we taking the dis?”

Bottom right text reads “Have your say at disabilitydebate.org” and “Disability Rights Commission”.

Right side is an image of a young person playing cards at a table with older people.

References

IPA | Disability Rights Commission: Are we taking the Dis?

DRC chief attacks lazy attitude over disability - Personnel Today